StubHub (NYSE: STUB) — Growth Optics, Governance Gaps, and the Cost of Trust

Author’s Note: We are short StubHub stock and stand to benefit if its share price declines. All information presented here is derived from public records and sources, which are cited in brackets. We invite readers to review these sources and form their own conclusions.

Executive Summary

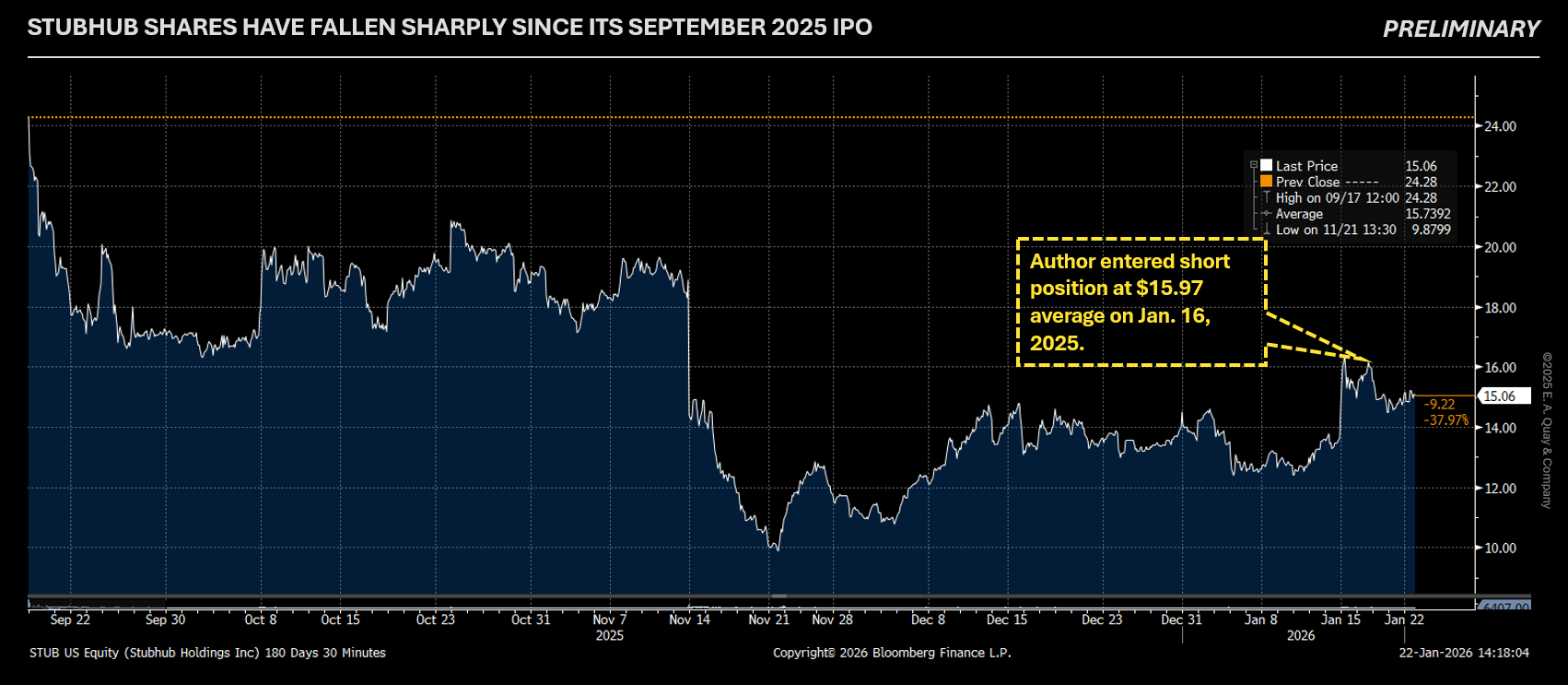

StubHub Holdings, Inc. (NYSE: STUB) is a newly public ticketing marketplace whose share price has fallen sharply from post-IPO highs (peaking near $23.50) to ~$15 today. This report presents a short thesis that challenges the optimistic narrative management is selling investors. We identify serious discrepancies in the founder’s story, concerning related-party dealings, a pattern of legal and regulatory troubles, and a breakdown in guidance credibility, all against a backdrop of heavy insider control and governance red flags.

What investors are being asked to believe: StubHub pitches itself as a resilient, high-growth marketplace that has integrated two global brands (StubHub and viagogo) and is poised to dominate live-event ticketing worldwide. Management touts strong cash generation and margin expansion, while emphasizing a “fan-first” mission. Investors are pointed to robust Gross Merchandise Sales (GMS) growth (up 11% YoY in Q3 2025) and a vast total addressable market for live event ticketing.

What history shows instead: StubHub’s past and present tell a more cautionary tale. The founding history has been controversially rewritten – CEO Eric Baker now claims to be the sole founder of StubHub, erasing co-founder Jeff Fluhr. The company’s origin and ownership timeline is complicated, including an ill-timed $4+ billion acquisition by Baker (via viagogo) right before COVID-19. Since going public in Sept 2025, StubHub has stumbled: it abruptly withheld Q4 guidance, prompting a 20–24% stock plunge and spurring class-action lawsuits alleging material omissions in the IPO prospectus. Meanwhile, multiple lawsuits and regulatory actions – from a $16.4 million jury verdict against StubHub for underpaying a partner to an Attorney General suit over “junk fees” – cast doubt on management’s rosy projections and commitment to transparency.

Key findings include:

Founder Narrative Issues: StubHub’s IPO filings credit Baker as sole founder and omit Jeff Fluhr, contradicting prior records. This revisionist history has drawn public rebukes from Fluhr and raises questions about management’s credibility (see Founder Narrative Discrepancy).

Related-Party Dealings: The CEO’s hedge fund, Andro Capital, actively trades tickets on StubHub’s platform, and StubHub paid Andro’s affiliate $1.6 million in 2023 for ticket inventory. Disclosures show complex agreements funneling ticket deals and financing through entities controlled by Baker. We examine whether these transactions were fully at arm’s-length and how “point-in-time” disclosure might obscure their true scale.

Post-IPO Red Flags: Shortly after IPO, StubHub halted forward guidance, citing unpredictable tour schedules. Analysts reacted with surprise and concern. At the same time, StubHub faces significant litigation: a jury verdict and other lawsuits total tens of millions in exposure, and the company has accrued >$60 million for legal contingencies including sales-tax disputes and regulatory fines. These factors call into question the reliability of management’s forecasts and the true “normalized” profitability.

Governance & Control: Baker holds super-voting Class B shares, effectively controlling the company. The largest outside shareholder is Madrone (Greg Penner’s vehicle) with ~22%; notably, Penner is the owner/CEO of the NFL’s Denver Broncos, raising questions about conflicts (Broncos tickets are presumably sold on StubHub). Recent abrupt board turnover (an “unexpected” director resignation ahead of earnings) has added to governance uncertainty.

Business Quality Check: The core secondary-ticket marketplace model, while high-margin, faces structural challenges. Take rates appear to be eroding slightly (StubHub’s take rate slipped from ~20% to 19%) amid competition and regulatory pressure for fee transparency. Growth is heavily driven by mega-tours (e.g. Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour inflated 2024 GMS; excluding it, GMS growth was actually much lower). We discuss whether the “flywheel” of fans and sellers is as strong as claimed, or if StubHub is increasingly reliant on professional brokers and related parties to churn volume.

Bottom line: StubHub’s stock appears to rest on a shaky foundation of optimistic storytelling and one-off boosts. We believe the discrepancies in the founding story, signs of aggressive financial engineering (e.g. delayed vendor payments boosting cash flow), and unresolved legal problems point to management integrity issues and a risk of further downside. In our view, STUB’s current ~$5.5 billion enterprise value is difficult to justify against the mounting red flags. We outline a downside valuation scenario where the stock could trade significantly lower if the market prices in more realistic growth and margin assumptions (see Valuation / Downside Framework). Near-term catalysts such as lock-up expirations, legal updates, or a guidance reset could further pressure the share price.

Overview and Business History

Corporate Origins: StubHub’s roots trace back to March 2000 in San Francisco, when Eric Baker and Jeff Fluhr founded the company as a pioneering online ticket resale marketplace. Baker, a Harvard graduate and former McKinsey consultant Bain Capital PE associate, conceived the idea in 1999 after struggling to find tickets for a Broadway show. He teamed up with Stanford Business School classmate Jeff Fluhr (Blackstone PE before his MBA) to develop the platform, with Fluhr dropping out of Stanford to become StubHub’s first CEO while Baker finished his MBA. The duo’s concept was simple but novel: create a trusted online exchange where fans could buy or sell live-event tickets with transparency and safety – a stark contrast to the opaque street scalping market of the era.

Original Name – Pugnacious Endeavors: Interestingly, the corporate entity behind StubHub wasn’t always so transparently named. In late 2004, Baker incorporated a new company called Pugnacious Endeavors, Inc. in Delaware. This entity would soon launch operations as “viagogo” in 2006 – an international ticket resale platform Baker founded after leaving StubHub. The pugnacious moniker (meaning “combative” or “eager to fight”) perhaps foreshadowed Baker’s aggressive re-entry into the ticketing arena following a falling-out with Fluhr. While the choice of name may have been a quirk or inside joke, it stands out as unusual for a consumer-facing business. Some observers have wondered if this oblique name was meant to conceal the venture’s identity during stealth development, or if it simply reflects the founder’s bold personality. In any case, Pugnacious Endeavors, Inc. – later renamed StubHub Holdings – now serves as the public holding company for the combined StubHub/viagogo enterprise. We discuss potential reputational implications in a later section (see Odd Original LLC Name).

Early Growth and eBay Acquisition: Under Fluhr’s leadership, StubHub grew rapidly in the early 2000s by tapping into sports and concerts fandom. By 2005 the company was reportedly cash-flow positive with ~$200 million in ticket sales, aided by strategic partnerships (it inked a deal with the Seattle Mariners as early as 2001). StubHub’s success attracted eBay Inc., which was looking to expand beyond auctions and into new commerce verticals. In January 2007, eBay acquired StubHub for $310 million in cash. This deal, championed by then-eBay executive (later CEO) John Donahoe, is often cited as one of eBay’s savvier acquisitions – a “tech M&A steal” given StubHub’s subsequent growth. StubHub became a crown jewel in eBay’s portfolio, continuing to thrive as a secondary-ticket marketplace under eBay’s ownership throughout the late 2000s and 2010s. Former Bain & Co. consultant and eBay executive, Chris Tsakalakis ran StubHub as President after Fluhr’s departure post-acquisition, and revenue hit ~$2 billion by 2014.

Eric Baker started his career as a strategy consultant at McKinsey and then worked at Bain Capital in 1999 when he hatched the StubHub idea. Bain Capital itself did not end up a major investor in StubHub’s early funding rounds (the seed was reportedly $600k in 2000, likely from angels and VCs). However, key influence emerged later: both Fluhr and Baker’s stints as a private equity associates at Blackstone and Bain respectively shaped the strategic direction of StubHub. Additionally, Bain & Co. consulting alumni have peppered StubHub’s management ranks over time. For example, Meg Whitman and John Donahoe – who orchestrated eBay’s StubHub purchase – were both longtime Bain & Co. executives (after leaving Bain a few years apart the pair sequentially held the role of CEO of eBay). These ties underscore a close network of elite PE/VC finance and strategy consulting through which StubHub’s story unfolded.

Viagogo and the Full-Circle Sale: After being ousted from StubHub in 2004 (more on that saga in the next section), Eric Baker moved to London and launched viagogo in 2006. Viagogo was essentially “StubHub for Europe,” exploiting the gap in the market that StubHub (then U.S.-focused) hadn’t yet filled. Over the next decade, viagogo grew into a leading secondary platform abroad, though not without challenges (growth eventually stalled and profitability was an issue by the mid-2010s). The fates of StubHub and viagogo dramatically converged in late 2019. That year, eBay – under pressure from activist investors (Elliott Management and others) – decided to divest StubHub as a non-core asset. In November 2019, viagogo (led by Baker) agreed to acquire StubHub from eBay for $4.05 billion. The deal closed on February 13, 2020 – literally weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down live events globally. This timing was disastrous: “the epically bad timing” became the stuff of Forbes case studies, as 95% of the combined company’s revenue evaporated overnight due to event cancellations. The acquisition was also subject to a lengthy review by the U.K. Competition & Markets Authority (CMA) given the combined firm’s dominance. For 18 months, StubHub and viagogo had to operate separately (with StubHub’s U.S. business essentially walled off from viagogo’s management) until CMA requirements were satisfied in September 2021. Integration was finally completed by late 2022.

Ownership Transitions & IPO: Post-merger, StubHub Holdings (the parent) was backed by a roster of institutional investors – including Madrone Capital (affiliated with Walmart’s Penner family), Bessemer Venture Partners, and WestCap – alongside Baker. By 2024 the company claimed to have regained momentum, citing internal metrics of growth and cash generation. StubHub filed for an IPO in early 2025 and completed the offering on September 18, 2025. The IPO offered at $23.50 raised roughly $1 billion (combined with a concurrent preferred equity from Madrone), and the stock debuted around $17 per share (opening day). Initial trading was strong – the stock popped above $20 – but since then the trajectory has reversed. As of this report, STUB sits below the IPO price, amid mounting concerns detailed below.

Framing the Investment Case: Investors today are effectively being asked to underwrite two decades of history – from dot-com era startup to eBay subsidiary to LBO and back to public company – on the belief that “this time is different.” Management’s implicit ask: ignore the checkered past (founder conflicts, legal battles, volatile earnings) and believe that StubHub is now a transformed, tech-enabled marketplace uniquely positioned for growth. This section provided the historical context; the following sections challenge whether the “new StubHub” narrative holds up to scrutiny, or whether history is indeed repeating itself (to shareholders’ detriment).

Post-IPO Lawsuits and Guidance Halt

StubHub’s short life as a public company has been turbulent. In the span of a few months after the September 2025 IPO, the company was hit with multiple lawsuits and made the controversial decision to suspend forward guidance, undermining investor confidence. We review these developments, focusing on what they signal about the reliability of management’s projections and the company’s risk profile.

(I) A Wave of Post-IPO Lawsuits:

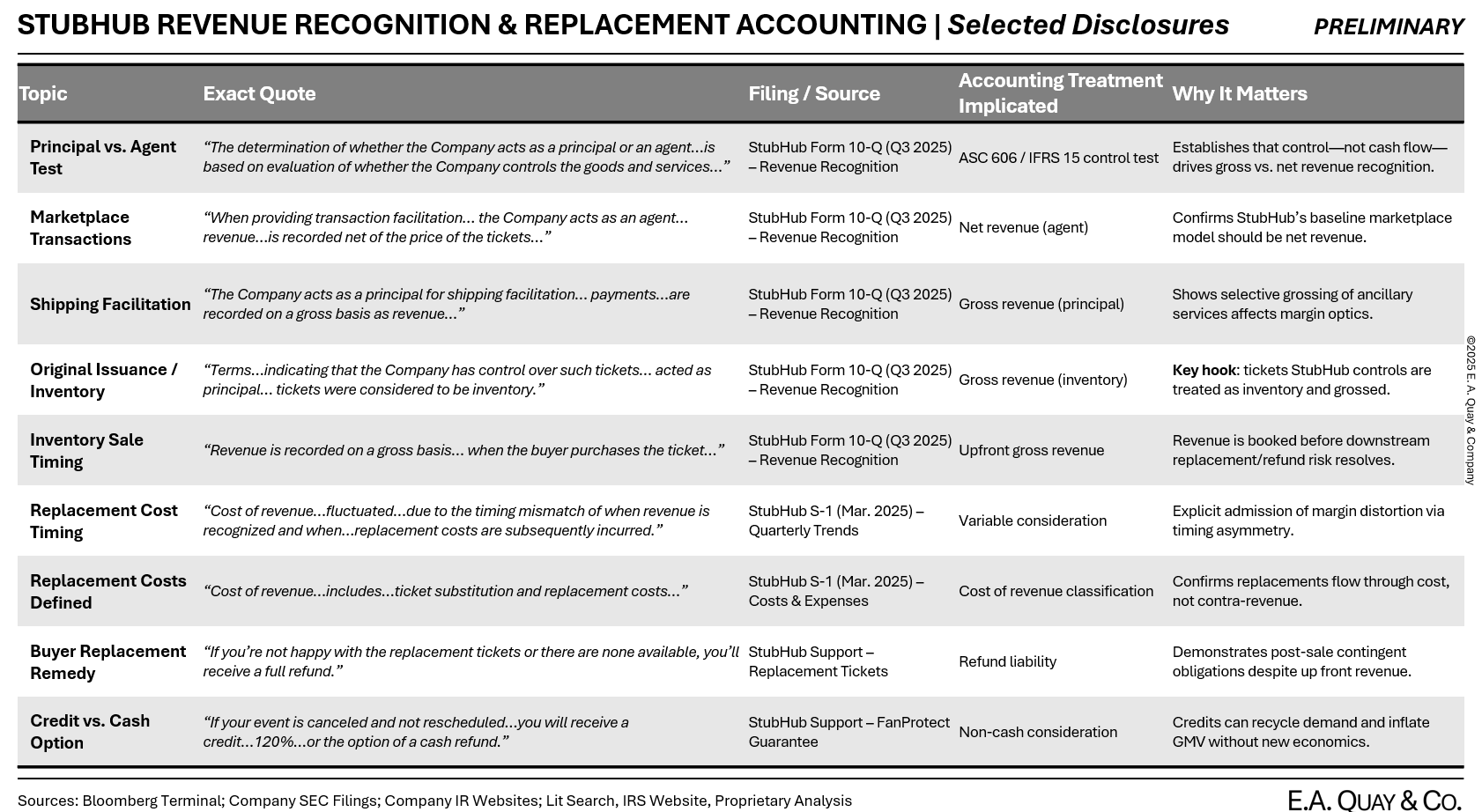

Not long after StubHub’s IPO, several shareholder rights law firms announced investigations and class-action lawsuits alleging that StubHub’s IPO registration omitted material information. By January 2026, at least one class action was filed in federal court, claiming StubHub’s IPO documents were false or misleading. The core allegation is quite serious: that StubHub failed to disclose “critical known trends” – specifically changes in the timing of vendor (ticket seller) payments that inflated its free cash flow in the run-up to the IPO. According to the complaint, StubHub had altered when it pays ticket sellers, which boosted trailing 12-month cash flow, but this change was not properly communicated to investors. If true, this would mean the rosy cash flow figures in the IPO prospectus were not entirely from organic growth or improved operations, but partly a result of stretching payables (effectively using sellers as a source of float).

The focus on seller payment timing resonates with industry context: StubHub (and peers) instituted a policy shift post-COVID to pay resellers only after an event occurs (to avoid the nightmare of clawing back payments for canceled events). This can temporarily improve marketplace cash flow (since buyers pay upfront, but sellers wait). The lawsuit suggests investors weren’t fully apprised of how this affected StubHub’s financials. StubHub has not yet substantively responded to these allegations publicly, but the stock’s reaction indicates the market is taking them seriously – STUB is down ~35% from its high, with some of that slide coming as these lawsuits were publicized.

In addition to investor lawsuits, StubHub faces material litigation from business partners and regulators:

Spotlight Ticket Management lawsuit: Spotlight (a corporate ticket management firm) sued StubHub in 2020, alleging StubHub underpaid commissions and interfered with Spotlight’s business. In May 2024, a jury rendered a verdict against StubHub for $16.4 million. StubHub had deemed the risk “remote” but lost – they’ve since posted a $24.6 million bond to appeal. The company has accrued the full $16.4 million as a liability on the balance sheet. This case matters not just for the money but for what it reveals: the allegations paint StubHub as willing to short-change a partner and meddle in contracts to its advantage. The loss also calls management’s legal risk assessment into question (they didn’t see this coming).

Regulatory actions on fee disclosure: On July 31, 2024, the Attorney General for D.C. sued StubHub for deceptive pricing, accusing it of a “convoluted junk fee scheme” – i.e., using drip pricing to hide fees until late in checkout. The D.C. lawsuit seeks to end these practices and impose penalties. StubHub’s response has been that it complies with laws while also (tellingly) launching an “all-in pricing” feature as an option – a likely attempt to preempt regulators. But the issue isn’t isolated: by August 2025, a U.S. regulator (likely the FTC) opened an investigation into StubHub’s advertised pricing practices. StubHub has already accrued $7.0 million as a probable loss for that matter. These regulatory pressures align with the U.S. government’s broader crackdown on “junk fees.” The upshot: StubHub may be forced to eliminate or reduce hidden fees, which could impact its take rate and profitability. Investors can no longer take the status quo fee structure for granted.

Other legal matters: StubHub’s Q3 2025 filing enumerated a litany of additional issues: an inquiry from a non-U.S. regulator about whether buyers were adequately shown the view from their seats (possible fine up to $12.9 million); a major sales tax dispute with a U.S. state (StubHub has reserved $51.2 million for this); a VAT dispute in Europe (reserved $30 million toward settlement); and even frozen funds in Switzerland and France related to consumer complaints about scalping practices at European soccer events (over $16 million frozen). The company insists these additional claims are not probable losses, but the sheer breadth of legal issues is striking. It suggests a pattern: StubHub has pushed boundaries on multiple fronts – fees, taxes, partnerships – and is now facing the consequences. For a newly public firm, the distraction and costs of these battles raise concern about management bandwidth and contingent liabilities.

(II) Guidance Halt and Earnings Credibility

Perhaps the most dramatic post-IPO development was StubHub’s decision not to provide forward guidance for Q4 2025 or beyond. On the Q3 2025 earnings call (Nov 13, 2025, the first as a public company), CEO Eric Baker and CFO Constance (Connie) James told analysts that due to volatility in event timing, they would refrain from giving a Q4 outlook. They explained that several large concert tours had gone on sale earlier than usual (in late Q3) and that this made Q4’s pipeline hard to predict. Baker framed it as taking a “long-term approach” rather than focusing on quarter-to-quarter predictions.

The market reaction was swift and negative. StubHub’s stock plunged 21–24% in one day following the earnings release. Wedbush analysts publicly expressed surprise and warned that “the lack of forward guidance will pressure shares” and fuel concerns about near-term visibility. Bank of America downgraded the stock after this event, as reported in financial media. Even though StubHub’s Q3 top-line results beat expectations (revenue +8% YoY to $468 million), investors fixated on the guidance void.

It’s highly unusual for a growth-oriented company to withhold guidance immediately after IPO – especially if business is as “phenomenal” as management claims. The decision prompted speculation: What is management seeing that they aren’t telling investors? Some possibilities:

Q4 softness: Live event ticket sales might be slowing more than anticipated, whether due to macroeconomic factors (e.g. consumer spending pullback) or tough comps (Q4 2024 had Adele, Taylor Swift tours, etc.). By not guiding, StubHub avoids confirming a slowdown.

Operational hiccups: The integration of StubHub and viagogo technology/platforms might be causing temporary issues (the company has been migrating systems). If so, management may lack confidence in forecasting.

Conservative posture due to lawsuits: With so many legal irons in the fire, perhaps management did not want to give any forward-looking statements that could be challenged later or that they might have to walk back if a big judgment/settlement hit.

Regardless of the reason, the guidance halt undermines trust. StubHub went public touting its adjusted EBITDA and free cash flow generation. Yet by the first quarter out, it retreated into opacity. This is especially concerning given that the IPO prospectus itself was very promotional (915-word “Our Story” with no mention of co-founder, lots of TAM talk) and is now alleged to have omitted key risk info.

Why this matters for forward guidance reliability: In the short thesis context, we interpret the guidance fiasco as a red flag about management’s credibility and internal forecasting ability. If StubHub’s business were truly on a steady, predictable trajectory, management would likely have issued at least a skeletal outlook. The refusal to do so suggests that either (a) demand is shakier than they want to admit, or (b) they themselves do not have good visibility – which is problematic for a company priding itself on data and dynamic pricing algorithms.

Moreover, the excuse given – that some tours shifted timing – rings hollow. Competitors like Ticketmaster or Vivid Seats did not make similar pronouncements; the live events industry always has some timing variability. One could argue StubHub used the earlier tour on-sales (e.g. some big tours in late September) to pad Q3, effectively borrowing from Q4, and didn’t want to guide down Q4. Notably, CFO Connie James said on the call: “It remains to be seen how this concert on-sale timing dynamic plays out in November and December”. That uncertainty was already “baked in” by the time of the call; thus the lack of guidance signals they feared the dynamic might leave Q4 light.

In summary, StubHub’s first report as a public entity raised more questions than answers. The legal overhang and the self-inflicted guidance debacle cast doubt on the reliability of any forward-looking statements from management. For a stock that still trades at a growthy multiple, this erosion of confidence is dangerous. The next sections delve into deeper issues that further undercut the management narrative – starting with a bizarre rewriting of StubHub’s very founding story.

Founder Narrative Discrepancy

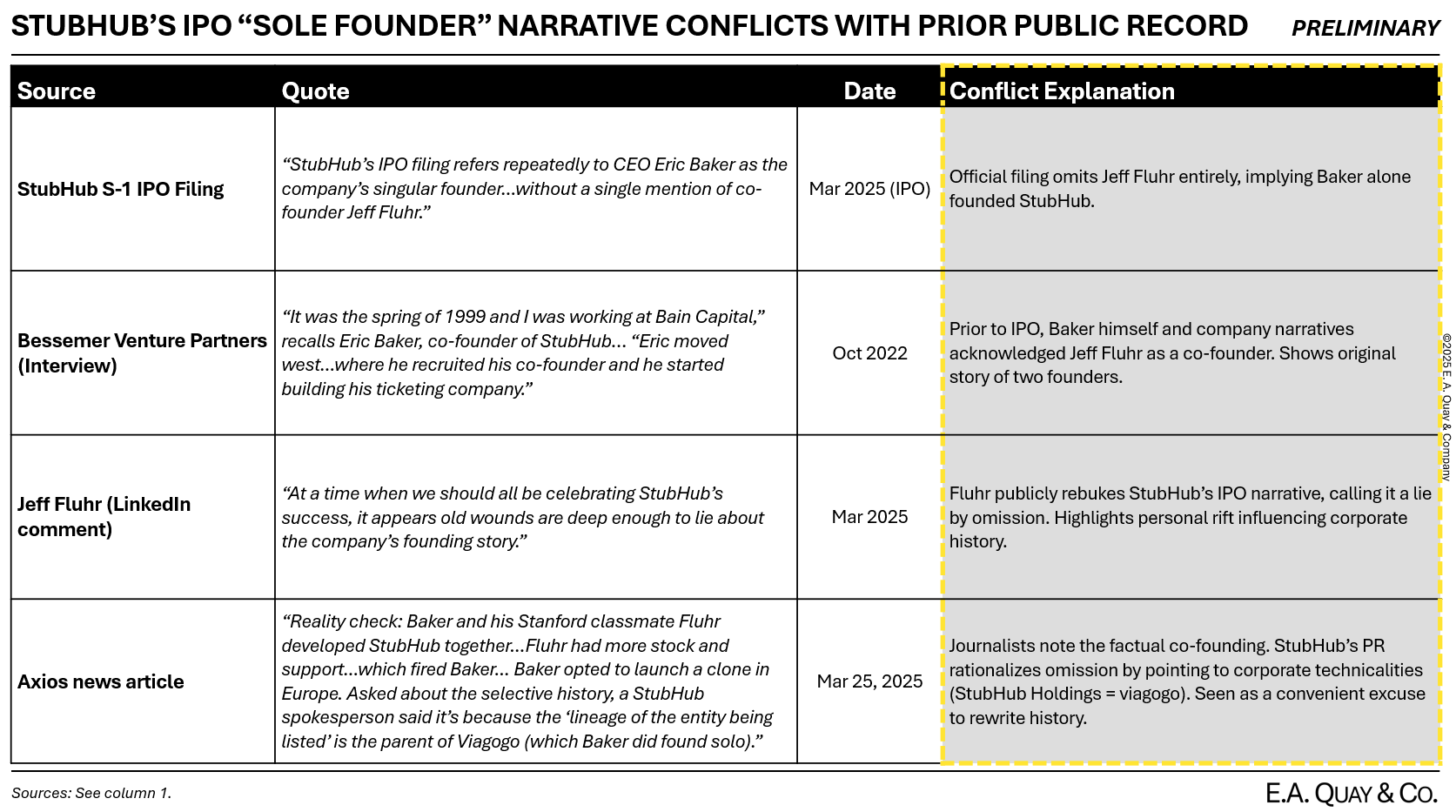

One of the more eye-opening revelations around StubHub’s IPO was the erasure of co-founder Jeff Fluhr from the company’s official history. In both the S-1 filing and public messaging, StubHub portrayed CEO Eric Baker as the “singular” founder. This contradicts well-documented history and even Baker’s own prior statements. The episode raises concerns about transparency and ego-driven management. Below, we present a table highlighting conflicting accounts:

Table: Conflicting accounts of StubHub’s founding, illustrating the discrepancy between the IPO narrative and historical fact.

As the table shows, historical fact is that Jeff Fluhr co-founded StubHub with Eric Baker in 2000. Fluhr was CEO until 2007 and instrumental in the company’s growth and sale to eBay. Baker’s attempt to claim sole founder status appears to be a result of personal animosity. The two founders famously fell out over strategy: Fluhr wanted to focus on StubHub’s brand and core business, while Baker pushed for partnerships (like with sports leagues) – this led to Baker’s ouster in 2004. No non-compete was put in place, enabling Baker’s revenge via viagogo.

The IPO “sole founder” claim is troubling for several reasons. Firstly, it suggests a willingness by management to distort the truth for vanity or marketing purposes. If Baker/StubHub will misrepresent something as basic as who founded the company, investors must question what else might be glossed over or spun. Indeed, Fluhr’s comment uses the word “lie” – an extremely strong language from a former insider.

StubHub’s justification – that technically the IPO entity descends from viagogo which Baker founded alone – is disingenuous. While the holding company lineage might be a legal fig leaf, the brand and business known as StubHub was co-founded by Fluhr. It is that brand equity and history that investors recognize. The attempt to conflate viagogo’s founding with StubHub’s origin is a sleight of hand. This is more than semantics; it shows how narrative can be manipulated when one person holds the pen (and in this case, super-voting shares).

From an investment perspective, why does this narrative discrepancy matter? It matters because it is symptomatic of a leadership approach that might prioritize ego and control over transparency. Baker’s control of StubHub (discussed further in Governance) means there are few internal checks on such messaging. If the CEO is willing to risk bad press and employee embarrassment (many early StubHub employees would know the truth) to aggrandize his role, one wonders how he handles less visible choices – like financial disclosure, related-party dealings, etc. In short, it’s a corporate governance red flag. Hindenburg Research, in a similar vein, often flags when a company’s narrative doesn’t square with independent records – viewing it as a sign of potential broader misrepresentation. Here, we have a concrete example in the founding story.

For completeness: Jeff Fluhr has moved on (he’s now a VC at Craft Ventures). He isn’t seeking any stake or credit beyond historical accuracy. That he felt compelled to speak out publicly indicates how egregious he found the IPO narrative. Investors should likewise ask: If management is playing fast and loose with the past, how confident are we in their representations about the present and future?

Related-Party Transactions & Disclosure Adequacy

One of the most concerning aspects we’ve uncovered is StubHub’s entanglement with entities controlled by its CEO, Eric Baker – specifically Andro Capital and its affiliate Colloquy Capital. These relationships create potential conflicts of interest and raise questions about whether StubHub’s marketplace metrics (and possibly financials) are being propped up by insider dealing. We examine what’s known from disclosures and why it might understate the true extent of related-party activity.

Who/what is Andro Capital? Andro Capital is a hedge fund or investment vehicle managed by Eric Baker (the name “Andro” appears to be used interchangeably for the fund and its management entity). Not much is publicly known about Andro’s external investors or scope, but it has been described as purchasing ticket inventory, presumably to trade or arbitrage on StubHub/viagogo. Essentially, Baker owns a ticket scalping fund on the side. In 2022–2023, Andro Capital was an active “seller” on StubHub’s platform.

Andro as a Seller & Fee Waivers: According to StubHub’s SEC filings, Andro engages StubHub to list, price, and fulfill tickets on its behalf – i.e., Andro acquires tickets and StubHub sells them through its system. The CEO (Baker) has an ownership stake in both StubHub and Andro. Notably, StubHub disclosed that it generated $0 in fee revenue from Andro’s ticket sales in 2024 and 2025 (through Q3), even though Andro was active (Andro had $0.1 million due to it from sales as of year-end 2024). This implies that StubHub waived or rebated its usual seller fees for Andro, or structured things such that no net fee was recorded. In 2022 and 2023, StubHub did report a token $0.1 million in fees from Andro’s sales each year – a trivial amount likely reflecting minimal friction.

The lack of fees is concerning because it suggests a preferential arrangement: regular sellers pay StubHub ~20% commission, but the CEO’s fund apparently does not. This could disadvantage shareholders (StubHub forgoing revenue) to benefit Baker’s fund, or could be intended to allow Andro to operate at scale on the platform with an unfair edge.

2023 Ticket Purchase – $1.6 million payment to Andro Fund: In March 2023, StubHub entered into a Servicing Agreement and side letter with “Andro STA Fund I”, managed by Andro. Under this deal, StubHub helped sell tickets owned by Andro. The kicker: when they mutually terminated this agreement early (in Dec 2023), StubHub paid Andro $1.6 million in fees during 2023. This appears to mean StubHub bought out or compensated Andro for something (perhaps unsold inventory or future considerations) – effectively StubHub’s cash going to the founder’s fund. Management claims no further fees are payable post-termination. The existence of this side deal was disclosed deep in the S-1 footnotes, but it’s unlikely many investors appreciated its significance: the CEO’s private fund was effectively flipping tickets through the company, and the company paid the fund $1.6 million. Even if this was at market terms, it’s a questionable practice. Why was StubHub, the marketplace, directly paying for inventory (behaving more like a broker) in one specific case? And why that inventory – was Andro stuck with tickets it couldn’t sell and Baker leaned on StubHub to bail it out? The optics are not good.

Ongoing Andro/Colloquy Programs: Rather than cease related-party dealings after the IPO, StubHub replaced them with a new structure. In July 2024, StubHub signed a Program Agreement with Colloquy Capital LLC, an affiliate of Andro. Under this program, StubHub refers certain ticket sellers to Colloquy for financing – essentially, if a ticket broker wants an advance on future sales, Colloquy (the Baker-affiliated lender) will front money and then get repaid from the ticket sale proceeds via StubHub. Colloquy takes a security interest in the sellers’ proceeds (it had $2.4 million collateral via StubHub as of Q3 2025). Then in March 2025, StubHub signed a Services Agreement with Colloquy, where StubHub will also help sell tickets that Colloquy itself owns (for a fee percentage).

So, effectively, Baker’s related entities now operate as a lender to StubHub’s sellers and as a consignment partner. Through Q3 2025, StubHub had earned $2.7 million in fees under these Colloquy agreements and owed Colloquy $1.6 million in proceeds due (plus $0.1 million in 2024). The numbers are still relatively small, but growing. The concern is twofold:

Conflict of Interest: Baker, as CEO of StubHub, can influence which sellers get referred to Colloquy and on what terms. Colloquy could cherry-pick the best brokers to finance (making low-risk loans) or get access to inventory streams, leveraging StubHub’s data. StubHub says no fees are exchanged between it and Colloquy for referrals, but Colloquy presumably profits from interest or spreads with those sellers. Is Baker effectively using StubHub’s market position to build a lucrative side business (ticket financing) for himself?

Obscured Volume and Economics: One might argue that as long as it’s disclosed, it’s fine. But we worry the disclosure is insufficient. For example, by saying “we generated $0 in fee revenue from Andro in 2024,” an investor skimming might assume Andro did nothing material. Yet Andro could have sold millions worth of tickets – only StubHub waived the fees. The economic throughput was there but doesn’t show in revenue. Similarly, the Colloquy program discloses only net amounts at period ends (e.g. $2.4M collateral, $1.6M due). We don’t know the total ticket volume financed or sold. It could be significantly higher. If, hypothetically, Andro/Colloquy are responsible for, say, 5-10% of StubHub’s GMV via these arrangements, that’s important to know – it would mean a chunk of StubHub’s marketplace is effectively controlled by the CEO’s fund. It also might mean the “real” take rate is lower (if fees are forgiven or kicked back to related parties).

Disclosure Adequacy: StubHub’s SEC filings do disclose these related-party items in the Notes. However, we question whether investors appreciate their implications. There was no prominent discussion of the conflict risk in the IPO Prospectus’s Risk Factors that we could find. It’s largely buried in Note 19 of the financials. The company’s response when asked (on the roadshow or by media) isn’t public, but this has become a talking point: at least one independent analysis flagged the Andro deals as a “red flag”.

From a short perspective, the related-party dealings signal that StubHub’s marketplace might not be as arm’s-length or pure as it appears. If growth in certain geographies or segments is lagging, Baker’s fund could be used to fill liquidity or inventory gaps, making metrics look better. Conversely, if Andro/Colloquy ever pulled back, StubHub could lose volume. It introduces an opaque support that investors can’t easily track. At worst, it could be used to stuff the channel – e.g., Andro buys tickets just to goose GMV (with no fees, low cost) and make growth look higher, then later StubHub quietly buys them back or subsidizes the losses via those side letters.

We are not directly accusing StubHub of fake sales – we have no evidence of that. But the infrastructure for potential manipulation or self-dealing is clearly in place. The prudent stance is to apply a governance discount to STUB’s valuation to account for this risk.

In summary, the Andro/Colloquy ties present both governance and economic concerns. They merit close scrutiny from analysts and possibly regulators (e.g., the SEC might inquire if revenue or user metrics are impacted by non-standard related-party terms). For investors, the key takeaway is that Eric Baker’s interests may not be fully aligned with public shareholders’ – he has his own side ventures intertwining with StubHub, and he’s shown willingness to have StubHub sacrifice some economics ($1.6M paid, fees waived) to benefit those ventures. That should give any independent shareholder pause.

Odd Original LLC Name

A minor but colorful detail: StubHub’s corporate predecessor was named Pugnacious Endeavors, Inc. This unusual name (misspelled by some as “Puganious LLC”) was the original Delaware entity Eric Baker formed after leaving StubHub the first time. While on the surface trivial, this tidbit has been brought up by some governance watchers as a curiosity – does it signal anything about the company’s culture or reputation?

Confirmation of Name and Purpose: The S-1 filing confirms that StubHub’s holding company was initially incorporated as Pugnacious Endeavors on Dec 17, 2004, and later rebranded. Essentially, when Baker started viagogo, he did so under this combative moniker (likely as a private corporate name not customer-facing). The Latin root pugnare means “to fight”; indeed, Baker was gearing up to fight his old company (StubHub U.S.) by launching a European competitor.

Implications for reputation/governance: In itself, an odd name doesn’t impact the business fundamentals. However, it reflects the founder’s mentality. “Pugnacious” suggests a willingness to be scrappy, aggressive, and perhaps to flout norms – traits we indeed observe in Baker’s style (founder disputes, regulatory run-ins). One might tongue-in-cheek say that a company literally born as “Pugnacious” might have a higher chance of confrontations – with regulators, competitors, etc. Sure enough, Baker fought a war of attrition with Fluhr, fought through a CMA probe, and is now fighting attorneys general. The aggressiveness can be double-edged: it helped him build two ticket empires, but it also yields the red flags we discuss throughout this report.

From a governance perspective, there is also a subtle point: transparency. When viagogo was operating in Europe pre-acquisition, few would have known about Pugnacious Endeavors, Inc. The use of a generic or stealth name could have been to avoid drawing attention, or just the founder’s personal touch. It’s reminiscent of how some companies use shell entities (with innocuous names) for various dealings – raising the question, does StubHub have any current subsidiaries or related entities with non-obvious names doing business? (One known subsidiary name: StubHub’s European arm was once “Noah Sarl” per EU filings; Colloquy and Andro are other examples of non-obvious affiliated names).

We are not suggesting anything nefarious about the name itself. At most, it’s a talking point that encapsulates the rebel streak in StubHub’s DNA. Investors might view that as positive (disruptor ethos) or negative (propensity for legal fights). Given the context of this report, we lean toward the latter interpretation: that Pugnacious Endeavors signaled an unapologetically aggressive approach that continues to influence StubHub’s governance – perhaps at the expense of prudence and compliance.

In conclusion, the “Pugnacious LLC” anecdote is a footnote, but one that fits the broader puzzle. It reminds us that this is not a buttoned-down, conservative management team; it’s one led by a founder-CEO who relishes a fight and often goes against the grain. That can yield great outcomes (as StubHub’s early success showed), but public market investors typically prefer a bit more predictability and compliance. Pugnaciousness in a public company, when taken too far, can translate to risk (e.g. regulatory fines, contentious relationships).

This context might help investors better understand why StubHub finds itself the target of multiple regulators – it’s baked into the culture from day one. Buyers of STUB stock should ask: Do I want my CEO to be “pugnacious,” or would I rather he focus on sustainable, transparent operations?

Business Model & KPI Reality Check

StubHub presents itself as a high-margin, growing marketplace benefiting from powerful network effects and secular trends (experiences over things, globalization of fandom, etc.). In this section, we examine the business model fundamentals and key performance indicators (KPIs) to see if they support the bullish narrative. The findings suggest a more mixed picture: growth is uneven and partly event-driven, margins are boosted by one-offs (and could be pressured by fee transparency efforts), and some KPIs hint at saturation or competition.

Marketplace Basics: StubHub operates a two-sided marketplace for secondary ticket sales (and increasingly some primary issuance via partnerships). Its revenue is primarily transaction fees – a cut from buyers and sellers on each ticket. Historically, StubHub charges buyers ~10% and sellers ~15% (percent of ticket price), though these numbers can vary. For ease, management often combines them into a single take rate (Revenue as % of Gross Merchandise Sales). In 2024, StubHub’s take rate was about 19% (on $1.77B revenue vs $9.3B GMV). This is slightly down from ~20% a couple years prior, suggesting some fee compression. Vivid Seats (competitor) by comparison had a ~12% take rate as it only charges the buyer (its fee structure differs). Ticketmaster in resale can be 20-25% (but Ticketmaster’s primary sales have different fees). StubHub positions its high take rate as evidence of pricing power and value-add, but one must consider regulatory and competitive forces that could push it lower.

Revenue & GMS growth drivers: StubHub’s reported growth has been strong as live events roared back post-pandemic. But it’s important to parse what’s organic vs. one-time. For example, StubHub highlighted that excluding the Taylor Swift “Eras Tour” phenomenon, its GMS grew 24% year-over-year, instead of 11% with Taylor included. Wait – usually you exclude a big outlier to show lower growth (if one event inflated numbers). Here they exclude Taylor to show higher growth, which implies the Eras Tour actually dragged down their YoY GMS growth percentage (because it made last year’s comps huge). Indeed, Taylor Swift’s tour drove an unprecedented surge in ticket sales in mid-2023 such that 2024 growth off that base was modest. This nuance indicates that StubHub’s growth is hit-driven. A few mega-tours or sports events can meaningfully swing GMS. It casts doubt on the idea of a smooth “secular” growth curve.

Additionally, user metrics are not disclosed in detail in public filings – which is telling. We don’t have recent numbers for active buyers or sellers from StubHub. (Vivid Seats, by contrast, reported 8.8 million active buyers in 2022, +11% YoY.) The omission might be because StubHub’s user growth is slowing or volatile. Anecdotally, after the pandemic shakeout, professional brokers may have consolidated (fewer sellers accounting for more volume), and some casual buyers may be using alternative platforms or primary ticketing channels. Without transparency on Monthly Active Users or repeat rates, we rely on revenue trends as a proxy.

JPMorgan Chase’s $300 Annual “StubHub Credit” is structurally different—and it matters for KPI quality: JPMorgan Chase (through Chase Sapphire Reserve and J.P. Morgan Reserve cards) now markets a recurring benefit: up to $300 per year in statement credits for ticket purchases made on StubHub and viagogo, delivered as two $150 tranches (Jan–Jun and Jul–Dec), with activation required and the benefit disclosed as available through 12/31/2027. Qualifying purchases are described as purchases made directly through StubHub/viagogo websites or apps and exclude gift cards; Chase also states it may reverse credits if an eligible purchase is returned/canceled/modified.

Chase announced its revamped Sapphire Reserve card on June 23, 2025, and disclosed that cardmembers who applied before that date would begin receiving the new benefits starting October 26, 2025.

That October activation timing is notable in the context of StubHub’s public-market debut. StubHub announced the pricing of its IPO on September 16, 2025, and stated the shares were expected to begin trading on the NYSE on September 17, 2025 under ticker “STUB.”

We’re not alleging any wrongdoing. We are highlighting a structural KPI risk: a large, bank-funded statement-credit program tied to a resale marketplace can mechanically increase reported marketplace activity—even when the “demand” is financially engineered by incentives.

Why this perk is different from most premium-card credits: Most premium-card “credits” are designed to be hard to cash out (e.g., travel incidentals, subscriptions, memberships). This one is different because StubHub’s product is itself a resellable asset: tickets.

StubHub explicitly describes itself as a marketplace where “fans are able to buy and sell tickets on demand” and where sellers can list and set prices, while StubHub handles marketing, payments, fulfillment, and customer support.

In the same IPO filing, StubHub defines Gross Merchandise Sales (GMS) as the total dollar value paid by buyers for ticket transactions (including fees charged to buyers and sellers, plus amounts remitted to sellers). The company also states that its revenue depends significantly on the dollar value of GMS flowing through its platform and its ability to generate fees from those transactions.

Separately, StubHub’s financial statement footnotes describe revenue as being “primarily generated” from facilitating ticket transactions, consisting “primarily” of fees charged to buyers and sellers when a transaction is executed (plus shipping fees charged to buyers).

Translation: If you subsidize transactions on a marketplace, you can subsidize (1) reported GMS and (2) transaction-fee revenue, at least mechanically, even if the incremental activity is not durable or repeatable without subsidies.

The “credit-churn” loop: how a $150 statement credit can create $300 of GMS: Chase’s benefit is a statement credit: the purchase posts to the card, and the credit is later applied (up to the cap). (Chase) That matters because (based on StubHub’s own definition) GMS is measured off the buyer-paid amount on the platform, not net of whatever rebates a bank may later provide to the cardholder.

Here is the simplest loop that this benefit makes possible in theory (not a claim that it is happening at scale):

Buy: A cardholder uses the Sapphire Reserve / J.P. Morgan Reserve card to purchase $150 of tickets on StubHub (a qualifying purchase under Chase’s terms, assuming activation and credit availability). The purchase posts as a StubHub transaction.

Subsidy: Chase applies a $150 statement credit (if the purchase amount is ≤ $150 and within the semiannual cap), making the cardholder’s net out-of-pocket potentially $0.

Resell: Because StubHub is designed for ticket resale, the cardholder can attempt to resell those tickets (on StubHub or elsewhere). If resold on StubHub for $150, that is another buyer-paid transaction on the platform.

Result (mechanically): StubHub would have facilitated two transactions totaling $300 of buyer-paid GMS ($150 buy + $150 resale), even though the first leg’s “consumer spend” may be entirely bank-subsidized.

Again, we are not claiming this is rampant. We are saying the structure allows for economically circular behavior that can add transaction volume, and management’s preferred KPI framework (GMS + transaction volume “flywheel”) is exactly where such behavior would show up.

Fees: why this can matter to revenue, not just “vanity volume”: StubHub’s IPO filing provides enough disclosed data to estimate how transaction volume translates into transaction-fee revenue.

From the S-1/A:

2024 GMS: $8,679,626 (in thousands) = $8.680B

2024 transaction fees revenue: $1,680,820 (in thousands) = $1.681B

Implied transaction-fee rate (transaction fees ÷ GMS): $1.681B ÷ $8.680B ≈ 19.4% (note: fees “can vary by transaction,” so this is an average).

Using that disclosed historical average purely as an illustration:

One $150 transaction implies roughly $29 of transaction-fee revenue at a ~19.4% rate.

Two $150 transactions (the churn loop) implies roughly $58 of transaction-fee revenue on $300 of GMS.

That gets you close to the intuition behind why this perk is dangerous for KPI interpretation: a bank-funded credit can produce real GAAP revenue for StubHub (transaction fees) while simultaneously inflating a headline marketplace KPI (GMS).

Why investors should care: this is a “quality of demand” question.

This Chase benefit creates at least three risks investors should not ignore:

KPI interpretability risk: If any meaningful portion of transactions are incentivized by statement credits, then reported GMS growth can reflect subsidy-driven velocity, not necessarily organic demand, pricing power, or lasting customer loyalty. (SEC)

Revenue quality risk: Because StubHub’s revenue is primarily transaction fees, subsidy-driven transactions don’t just “pad volume”—they can also drive recognized revenue. (SEC)

Program dependence risk: Chase discloses this StubHub/viagogo credit as available through 12/31/2027, but this is still a contractual/marketing construct that can be changed, not a structural competitive moat. Put bluntly: if a portion of post-IPO “momentum” is coming from a premium credit-card rebate machine, investors should demand transparent disclosure on how much, at what cost, and with what controls.

What StubHub does not clearly disclose (and what investors should demand): In StubHub’s IPO materials, we did not find clear disclosure (at least in the portions reviewed here) that quantifies the economic impact of this specific Chase benefit—despite the obvious potential to affect marketplace KPIs and customer acquisition optics. (If StubHub later discloses this in post-IPO filings, it should be added here.)

At minimum, investors should want the following program-level disclosures (whether in MD&A, risk factors, or KPI discussion):

Volume attribution: What % of GMS and orders are tied to Chase Sapphire Reserve / J.P. Morgan Reserve credits?

Unit economics impact: Are any fees reduced/waived for credit-driven purchases? Does the mix shift take rate? (StubHub says fees vary by transaction; investors need to know how the credit program changes that mix.)

Cost-sharing economics: Who funds the $300 credit economically—Chase, StubHub, or a blend? If StubHub funds any portion, where is it recorded (marketing expense, contra-revenue, partner allowance)? (Not alleged—this is a disclosure request.)

Controls / abuse monitoring: What controls exist to detect circular trading, self-dealing, or other “perk monetization” behavior that creates synthetic GMS without incremental end demand?

Seasonality and pull-forward: Do GMS and transaction-fee trends show spikes around June 30 and December 31 that are attributable to credit expiration dynamics?

Customer Remediation Friction: Last‑Minute Fulfillment, “FanProtect” Reality, and an Arbitration “Catch‑22”

StubHub sells investors a story of a scaled, trusted marketplace. But the real product in secondary ticketing is not the website—it’s reliable fulfillment under time pressure and credible remediation when things go wrong. Recent public narratives (admittedly anecdotal) suggest the opposite: (i) orders and parking passes not in hand until hours before kickoff, (ii) customers traveling without certainty they can access what they paid for, and (iii) consumers alleging a procedural “catch‑22” where they are contractually pushed into arbitration yet claim StubHub is difficult to serve with required notices to even start arbitration.

Example 1 | National championship “ticket failure” headlines (operational + reputational risk): On January 19, 2026, BroBible reported that “a large number of fans” who purchased tickets for the College Football Playoff National Championship (Miami vs. Indiana) were still uncertain about getting into the game—highlighting scenarios where orders were not fulfilled and where buyers faced day‑of‑event anxiety around ticket delivery and parking access.

The article specifically describes:

A buyer who claimed their order (placed more than 48 hours earlier) was not fulfilled and was later told StubHub “can’t fulfill the order,” after traveling to the event location.

A timing dynamic where, according to the article, sellers had until roughly two hours before kickoff to transfer tickets and parking passes—creating a structurally stressful “limbo” for traveling customers who want to tailgate or simply plan their day.

Parking-pass issues where some buyers allegedly received offsite substitutes (e.g., a ParkWhiz pass) rather than the expected stadium-lot parking, with the author asserting that parking passes were “not verified as legit.”

Separately, the author asserts that StubHub has shifted toward canceling sales, charging sellers a “200%” penalty, and refunding purchasers—implying a remediation approach that may prioritize refunds and seller penalties over true like‑for‑like replacements. We have not independently verified this operational policy or the economics described, but the reputational point stands: high‑profile event-day fulfillment failures become public instantly and can drive negative brand awareness at the exact moments when StubHub is trying to expand its consumer funnel.

Click to expand image. CFP Ticket Issue.

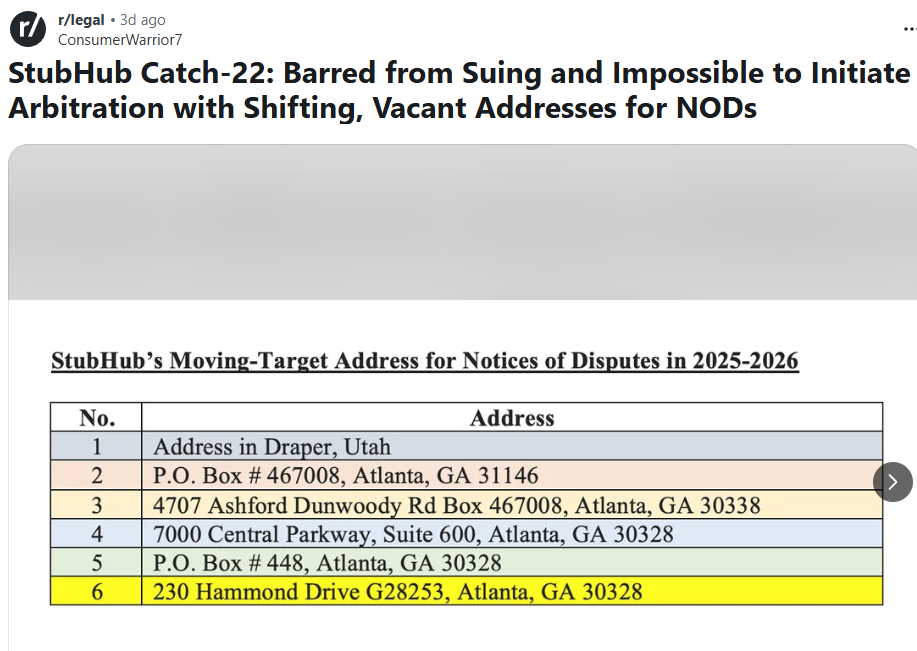

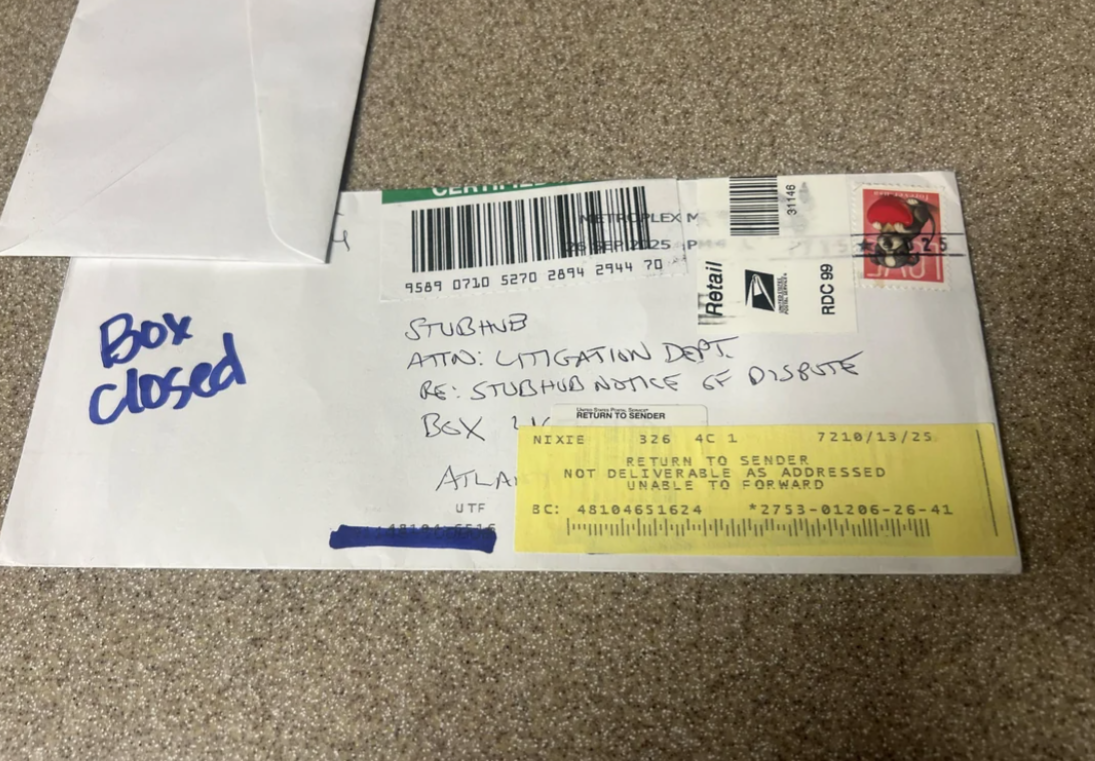

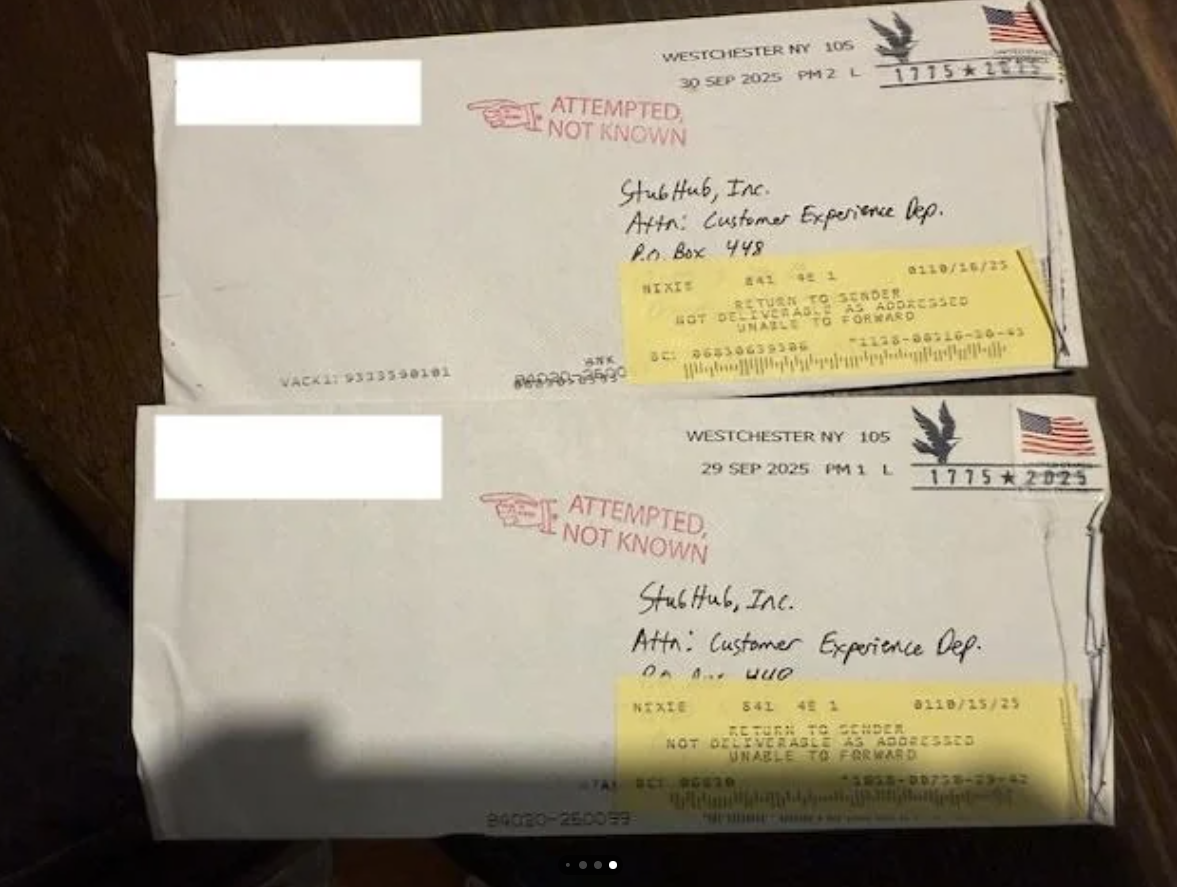

Example 2 | “Arbitration catch‑22” allegations (consumer deterrence risk): A Reddit post titled “StubHub Catch‑22: Barred from Suing and Impossible to Initiate Arbitration with Shifting, Vacant Addresses for NODs” alleges that StubHub has used “six different addresses” for notices of dispute and that some past addresses were “vacant, inaccessible, or nonexistent.” The post further alleges that even the “current address” created delivery issues (the user claims USPS did not recognize part of the address), despite a user‑agreement requirement for 30 days’ notice and use of certified mail.

The same post also alleges that, even when consumers do reach arbitration, StubHub “has refused to pay AAA fees in several cases,” which the author claims led to cases being thrown out and consumers needing to re‑file. We cannot verify the underlying facts from this post. However, if even partially accurate, it creates a material reputational and regulatory vulnerability: it frames the company’s dispute-resolution process as intentionally frustrating for consumers—exactly the kind of narrative that can attract regulator interest and class-action lawyering in consumer-facing categories.

Click to expand image. Arbitration issue.

Example 3 | Chase-Sapphire-channel customer complaints (brand risk amplified by the partnership): The timing here matters. StubHub is now being pushed directly into a premium consumer channel via Chase’s “ticket credit” marketing. In that context, it is noteworthy that a post in r/ChaseSapphire titled “StubHub Refused to Settle with Victim for $5,600, Then Paid the AAA and Arbitrator $28,700…” alleges a dispute in which StubHub refused to settle for $5,600 and instead incurred substantially larger arbitration-related costs.

In the comment thread, the same user argues: “SH could have paid $5,600 to settle the whole thing” but instead paid $5,600 “+ $28,700 to AAA and arbitrator + interest + victim’s attorney fees + SH attorney fees + SH attorneys’ travel and other expenses.” Other commenters in the thread challenge the completeness/accuracy of what was posted and ask for the final arbitration award—underscoring that this is an allegation, not an established fact.

The post also explicitly ties the issue to the Chase partnership: the author states, “Chase Sapphire people need to know what risk they take when they deal with SH because of that shiny credit offer.”

Click image below to expand it:

Why this matters to the short thesis (even if each anecdote is “just a story”): We are not claiming these stories are statistically representative. We are highlighting an investor blind spot: StubHub does not appear to provide the operating metrics investors would need to independently evaluate “trust” at scale—and absent disclosure, the market is forced to infer quality from stories like these.

If the customer experience is deteriorating, the downstream impacts can include:

Higher refund/chargeback rates and increased customer support burden (direct margin pressure).

Lower repeat usage and higher CAC to replace churned users (marketing efficiency pressure).

Regulatory scrutiny risk if dispute-resolution processes are perceived as deterrent or deceptive (headline and compliance cost risk).

KPI quality questions: if growth is partially incentive-driven (e.g., through card credits) while customer remediation is strained, reported GMS can look fine even as trust and retention deteriorate underneath.

Profitability – quality of earnings: StubHub touts adjusted EBITDA margins in the mid-teens and strong free cash flow conversion. However, recall that Q3 2025 included a massive stock-based comp expense (~$1.4B) related to the IPO vesting. On an adjusted basis this is stripped out, but that expense will manifest as dilution. Indeed, shares outstanding have ballooned (partly from preferred stock conversions). So while free cash flow was $255M in 2024 (per mostlymetrics), that didn’t account for a likely increase in shares by 2026 due to RSU vesting, etc.

Also, part of StubHub’s profitability came from heavy cost cuts during COVID and the integration. Baker slashed headcount and costs to turn viagogo + StubHub from money-losing into money-making by 2023. That’s commendable, but one must ask if those lean costs are sustainable. Already we see general and administrative (G&A) expense ballooned in 2025 due to legal reserves. Sales and marketing might rise as they try to grow internationally (where brand recognition isn’t as strong as in the US). StubHub spent years under eBay with virtually no marketing (eBay’s platform drove traffic). Now, as an independent, it may need to invest more to stay top-of-mind, especially if Google SEO/SEM costs increase.

Competition and Market Share: StubHub remains the largest secondary ticket platform in North America by most measures. Vivid Seats, SeatGeek, Ticketmaster Resale, and a slew of smaller sites (including team exchanges) compete. There’s evidence StubHub lost some share during its integration chaos (2020-2021) to Vivid and SeatGeek. For instance, SeatGeek won big primary deals (NFL teams, the Dallas Cowboys, etc.) and built a user base that way. StubHub partnering with MLB for primary tickets (starting 2026) is a move to fight back. But the business model is blurring: StubHub dipping into primary issuance (via “direct distribution” deals) puts it in more direct competition with Ticketmaster on primary, which is a new challenge and not one to underestimate – Ticketmaster/Live Nation are formidable and have the ear of many content rights holders. If StubHub can’t secure more primary supply, it remains dependent on brokers and individuals listing inventory. Those sellers are not loyal; they will cross-post tickets on multiple sites to get the best net price. This dynamic tends to squeeze margins over time (if one platform charges too high a fee, buyers/sellers migrate to another with a better net deal).

Conversion rate & user experience: A key KPI for marketplaces is conversion (how many site/app visits result in a purchase). StubHub historically benefited from extremely high intent traffic (someone comes looking for tickets to X, they usually buy if price is okay). Conversion is partly why StubHub could charge high fees – once a fan is on the site with a credit card out, the extra $20 fee might not deter them. However, the industry’s pivot (voluntarily or by law) to upfront all-in pricing could reintroduce price comparison behavior. If StubHub shows $120 total and SeatGeek shows $115 for the same section, conversion could shift. The threat here is that fee transparency could commoditize the inventory – making price competition more direct. StubHub would argue its scale and trust keep users sticky. But as someone who ran large ad campaigns for ticket marketplaces, I know a lot of users simply click the first Google result or use aggregators (e.g., TicketNetwork feeds) that show multiple marketplace listings. StubHub’s brand got dinged by the years of drip pricing (see D.C. lawsuit) – many fans know to check alternatives to avoid high fees.

International expansion reality: StubHub often cites growth potential in Asia, LatAm, etc. The reality is that outside North America and Western Europe, the secondary market is nascent and often illegal or culturally frowned upon. Viagogo did expand globally but also faced heavy backlash (e.g., banned in Italy for some time, scrutinized in Germany, etc.). The “fragmented offline international market” argument implies upside, but cracking those markets costs money and faces regulatory risk (for example, some countries cap resale prices or require local partnerships).

In summary, the business model is profitable and has strong aspects (network effects: large inventory attracts buyers, and buyer traffic attracts sellers – a virtuous cycle). However, key KPIs show maturity and pressure:

Take Rate: slight decline, and likely more decline if forced to display lower fees or offer incentives to sellers.

GMS Growth: heavily dependent on blockbuster tours and favorable post-COVID demand, which will normalize. Also, sports may face headwinds if teams do poorly (ticket demand correlates with team performance too).

Active Users: undisclosed, possibly plateauing; competition for new younger users (Gen Z) is intense, with rivals like TickPick (no-fee model) gaining some traction via word-of-mouth.

Geographic mix: U.S. is majority of business; Europe recovering; Asia minimal. StubHub can tout “200 countries served” but the revenue is concentrated. For instance, UK is a big market via viagogo, but that business had to be partially separated by CMA (viagogo sold StubHub’s international arm to Digital Fuel in 2021 as a remedy – though I’m unsure if that completed or got reversed later). If some parts of international aren’t fully integrated, growth there might not accrue wholly to STUB shareholders.

Ultimately, the KPI reality check tempers the bull case that StubHub is a pure growth story. It looks more like a cyclical marketplace with moderate growth at best in a normal year, high operating leverage (good for profits in boom, bad in bust), and increasing regulatory friction. This is not to say StubHub can’t succeed – it likely will remain a prominent platform – but the risk is the market was treating it like a high-growth tech IPO, whereas it might behave more like an ebbs-and-flows business tied to concert touring cycles and sports seasons.

For a short thesis, this suggests that Street expectations might be too high. If analysts modeled, say, 15% sustained growth and gradually expanding take rates, those models may be due for downward revision. A single disappointing concert season (or a recession reducing discretionary event spending) could cause StubHub to miss numbers. Without guidance, analysts are flying a bit blind, which means surprises (negative) are more likely. If and when STUB has a soft quarter or cuts outlook, the stock could re-rate significantly, especially given the governance issues that make many fundamental investors already hesitant.

Red Flags & Governance

We’ve touched on several red flags throughout this report – now we compile and expand on them in one place, focusing on governance issues and signals of risk that extend beyond pure numbers. Good corporate governance is especially critical for a company like StubHub, which operates a marketplace where trust and fairness are paramount. Unfortunately, we see multiple governance red flags:

Dual-Class Share Structure (Founder Control): StubHub went public with a dual-class share system. Eric Baker owns Class B shares with 100:1 voting power (as per the prospectus) such that Class B controls ~87% of voting rights. This means public Class A shareholders have virtually no say in corporate matters – the founder can single-handedly elect the board, approve mergers, reject shareholder proposals, etc. While dual-class structures are not uncommon in tech IPOs, they are often viewed negatively if there isn’t clear alignment and exceptional leadership. In StubHub’s case, Baker’s track record (e.g., being fired once, rewriting history) doesn’t instill confidence that unchecked control will be benign. The dual-class structure is set to last indefinitely (usually via a sunset clause after X years or if founder stake falls below a threshold – but none was clearly outlined). Investors thus are at the mercy of Baker’s decisions.

Board Composition and Turnover: Post-IPO, StubHub’s board included Eric Baker as Chairman, and representatives from major pre-IPO investors. In theory, those investors should be independent-ish voices. However, any Class B holder can override board actions de facto. We note that one board member (Finnegan) resigned in March 2025 (pre-IPO) for unspecified reasons. Sudden board departures can indicate disagreement or governance stress. It’s also worth noting that Baker’s personal style – he’s known to be very demanding – could lead to high turnover in key roles. For instance, StubHub went through multiple CFOs in the run-up to IPO (at least one CFO, Ajay Gopal, left during the pre-IPO phase; Connie James came on board only in 2023).

Executive Team Depth: The current president of StubHub is Nayaab Islam (promoted internally after a previous president left). The bench of experienced public-company executives is a bit thin. Baker is an entrepreneurial leader but has less experience running a U.S. public company; the CFO James is seasoned (ex-LifeLock/CheapTickets) which is a plus. However, given the complexities (global ops, legal issues), one wonders if the management team has adequate breadth. The departure of Sukhinder Singh Cassidy (former StubHub president under eBay) in late 2020 and other experienced hands means Baker has a lot of direct reports who are relatively new to this scale.

Regulatory Compliance Culture: The laundry list of legal issues (fee displays, taxes, etc.) implies that StubHub has historically taken a reactive approach to compliance – pushing the envelope until challenged. A proactive governance culture would anticipate these things (e.g., all-in pricing without being forced, paying required taxes rather than waiting for an audit). The fact that $51M had to be reserved for sales tax only after an audit suggests compliance gaps. Similarly, being sued by DC rather than settling or changing practices earlier shows either hubris or misjudgment. Governance-minded investors will worry that this culture could lead to more penalties or brand damage.

Shareholder Alignment and Related Parties: We discussed Andro and Colloquy – clear conflicts where the CEO’s interests could diverge from shareholders’. Another angle: Madrone/Greg Penner. Penner, as noted, is owner of the Denver Broncos. It’s not inherently a conflict to own both a team and a resale marketplace stake – but consider that NFL has its own authorized resale (Ticketmaster NFL Ticket Exchange). Broncos tickets do appear on StubHub as resale (though the NFL tries to funnel through official channels). Could Penner’s dual role influence StubHub’s strategy? For instance, StubHub might pursue partnerships with teams or offer favorable terms, etc., that benefit owners. There’s no evidence of wrongdoing here, but it’s an unusual overlap. Typically, team owners shun secondary markets (they want primary sales); Penner now profits from secondary fees too. If anything, this could raise league-level governance questions – but in terms of StubHub, having a powerful shareholder who is not primarily focused on StubHub (Penner’s day job is Walmart chair and NFL owner, not a StubHub exec) might limit the attention he pays to StubHub governance beyond his initial investment.

Transparency and Communications: We give low marks here. The IPO prospectus arguably left out the full story on key issues (see class action claims). The Q3 communications were bungled with the no-guidance approach. The company does not provide the granular KPIs (buyers, take rate breakdown, etc.) that one would like to evaluate health. For instance, they tout “over 1 million sellers and 40 million tickets sold in 2024”, but how many buyers? How many were repeat vs new? Not disclosed. Fine – maybe competitive reasons – but it feels like they’d rather tell a controlled narrative (like the founder story, or cherry-picked stats like “24% ex-Taylor growth”) than a consistent, GAAP-like set of metrics each quarter.

Audit and Controls: As a new public entity with legacy of private equity ownership, one might be cautious about internal controls. They’ve had to integrate financial systems of viagogo and StubHub, which were separate for a long time. The risk of a material weakness in controls or restatement is non-zero in such cases. We haven’t seen anything yet, but any misreporting on revenue recognition (especially with all the deferred revenue from ticket sales prior to events) could be a watchpoint. Also, the heavy use of non-GAAP metrics (Adjusted EBITDA, Adjusted FCF) means we must trust the adjustments are appropriate. Given the litigation reserves and stock comp, there’s plenty of room for “massaging” adjusted figures (e.g., excluding all legal expenses as one-time, even though they seem recurring).

In sum, StubHub’s governance profile is poor: founder-controlled, conflict-rich, and historically combative with stakeholders. For investors, this warrants a higher discount rate and a cautious stance. We’ve essentially got a founder with a vendetta (to show he can run StubHub better than when he was fired) using public money to prove a point, and along the way he’s comfortable skating close to ethical lines (erasing a co-founder, cutting side deals). That combination can sometimes produce outsized results, but it can also end in scandal or value destruction if unchecked.

A telling indicator will be how StubHub responds to the current challenges: Will they settle major lawsuits proactively or keep fighting? Will they institute all-in pricing globally (even if it cuts volume short-term) or drag feet? Will they begin providing guidance again or continue to avoid accountability for forward-looking statements? Their choices will signal whether any governance improvements are happening. So far, we see little evidence of change.

Catalysts

A short position in STUB will likely require catalysts to drive further share price decline. Here are potential catalysts on the horizon:

Lock-up Expiration and Insider Selling (March 2026): Typically 180 days post-IPO, early investors and insiders can sell. For StubHub, that should be around mid-March 2026. Madrone (Penner) and other large holders may trim positions. If they do, it could flood the market with supply and signal a lack of confidence. Even the anticipation of lock-up expiration often pressures stock prices in the months prior.

Earnings Miss or Guidance Reset: If StubHub resumes giving guidance and that guidance is below consensus, or even if they continue to withhold guidance and analysts downgrades follow, the stock could slide. The first full-year outlook they provide (possibly in Q4 2025 or Q1 2026 results) will be critical. A miss on Q4 2025 numbers (to be reported likely Feb 2026) combined with cautious commentary could be a catalyst.

Legal/Regulatory Outcomes: Any adverse ruling or settlement news can be a negative catalyst. For instance:

The D.C. AG case might settle with StubHub agreeing to pay fines and display all-in pricing. Announcement of a, say, ~$5M fine and mandatory fee changes (especially if applies beyond D.C.) would underscore regulatory risk.

The Spotlight appeal – if StubHub loses again or drops appeal and pays $16M – while reserved for, would remind investors of these costs.

The status of the FTC (or other regulator) investigation into fee practices: a formal action or expanded probe could scare investors, akin to what antitrust news does to tech stocks.

The outcome of the sales tax dispute (if they have to pay more than reserved, or if more states line up with claims).

Economic Downturn / Event Cancellations: Should macro conditions worsen (higher inflation squeezing discretionary spend, or a mild recession), live event ticket sales may decline. Evidence of softness – e.g., Ticketmaster or Live Nation commentary that concert ticket sales are down – could read through bearishly to StubHub. Additionally, if any major events get canceled (pandemic relapses or other shocks), it reminds the market how vulnerable the model is (recall how Covid nearly killed the company in 2020).

Management/Board Changes: While less likely, a resignation of a key executive “to pursue other opportunities” could trigger alarm. For example, if CFO Connie James were to resign early in 2026, investors might worry about internal issues. Similarly, if a board member publicly steps down citing disagreement, that would be a red flag catalyst.

Analyst Downgrades or Short-Seller Reports: Currently, only a handful of banks cover StubHub. If any change their tune (e.g., BofA already downgraded after Q3, others might follow suit if numbers don’t improve), it can move the stock. This report you’re reading itself could serve as a catalyst if it circulates widely (though we are not affiliated with any of the big activist short firms, we modeled it after their style). Even a mention on financial media (CNBC, etc.) of “governance concerns at StubHub” could catch attention.

Competitive Developments: If a competitor makes a bold move – for instance, SeatGeek (private) announces a major new partnership or funding round, or if Ticketmaster revamps its resale such that it cuts fees to undercut StubHub – the competitive threat becomes more tangible. Also, any legislative action on ticketing (e.g., a federal bill mandating all-in pricing or capping resale fees) could be a catalyst; these things are being discussed in Congress in the context of “junk fees” initiatives.

Macro Market Sentiment Shift: In a broad sense, if the market rotation continues away from speculative growth to value, companies like StubHub (which went public into a not-so-frothy tape) could still see multiple compression as part of that trend. This is more diffuse, but sometimes there’s a moment where the market “decides” to re-rate a whole cohort of recent IPOs to more conservative valuations.

In terms of timeline, the next 3-6 months hold several likely catalysts: Q4 earnings (Feb), lock-up (Mar), any legal updates in that window, and perhaps a first full-year guidance (if they give one by Q1 or Q2 2026). This aligns well with a short thesis timeframe.

One should always be aware of short-term counter-catalysts too: e.g., if Live Nation posts blowout earnings or some superstar announces an unexpected huge tour, the sector might rally (StubHub could piggyback on that optimism). We regard those as opportunities to add to a short at higher levels, assuming the structural issues remain.

In summary, the catalyst path appears actionable and not too far out. The combination of insider selling windows and likely disappointing operational news forms a credible thesis for share price decline in the near to medium term.

Risks to the Short Thesis

No short thesis is complete without acknowledging what could go wrong (for the short) or where our analysis could be off. StubHub, as a business and stock, does have factors that could buoy the price or invalidate some of our bearish expectations. Key risks to consider:

Continued High Demand for Live Events: We may be underestimating the secular strength of the live entertainment cycle. Post-pandemic “revenge spending” on concerts and games might persist longer. If 2026 sees another wave of blockbuster tours (e.g., another Taylor Swift leg, big reunions, etc.), StubHub’s volumes could surprise to the upside. High demand could also give StubHub leverage to maintain its take rates even with all-in pricing (if everyone is doing it and events still sell out, fee pressure might not materialize strongly).

Management Could Adapt Successfully: While we’ve criticized management’s choices, they could course-correct. For instance, Baker might bring in more seasoned executives or cede some control (though dual-class remains). They might settle lawsuits in a way that clears the overhang relatively cheaply. If they begin issuing guidance and meeting it consistently, trust can rebuild. Essentially, they could take the Hindenburg/Muddy Waters critiques as a wake-up call and improve governance. Short sellers often assume management won’t change, but occasionally they do.

Lack of Near-term Negative Surprises: We’ve enumerated potential legal or earnings pitfalls. It’s possible none of these hit in the near term. The DC lawsuit may drag on without resolution (no fine yet), the FTC may just result in an agreement without major financial hit, and Q4 might come in okay if Q3 pulled forward some sales but Q4 had other events (e.g., some Taylor Swift international dates went on sale in November – could boost Q4). If StubHub muddles through without any shock, the stock might drift or even grind up if the market moves up.

Acquisition or Take-Private: There is an outside chance that some entity might attempt to acquire StubHub at a premium. While antitrust rules out Live Nation and perhaps other big players, a private equity consortium could be interested if the price falls enough. Remember, StubHub was private-equity owned until just recently. If the stock dips, say, to $10, Baker and his investors might think about taking it private again to avoid public headaches (especially if Baker sees long-term value). They’d have to pay a premium (maybe $13-15), which from current price isn’t huge but from a theoretical $10 would be 30-50% premium. That scenario caps downside for shorts. However, it’s a bit speculative given they just IPO’d and have cash to pay down debt now.

Strong Partnerships / New Revenue Streams: StubHub could pleasantly surprise with new business lines or deals. For example, their MLB primary partnership from 2026 might lead to more deals (maybe the NBA or NCAA deals down the line). If StubHub shows it can encroach on primary ticketing (even moderately), that could unlock more revenue streams (e.g., splitting primary fees with leagues). Also, StubHub has a lot of user data – they could monetize via targeted promotions, or dive into event financing, NFTs/ticket authenticity blockchain (hyped concept but who knows). If any such initiative is announced and believed by the market, it could spur optimism.

Short Squeeze / Technicals: The short interest on STUB is not publicly known yet (since it’s new, initial reports show relatively low short interest). But if our thesis gains popularity and many short the stock, one risk is a squeeze. With a low float (many shares locked with insiders, and Baker won’t sell Class B), the tradable float might be only a couple hundred million shares. If someone decided to run a squeeze (hypothetically, a meme stock crowd if they noticed heavy shorting and low float), the stock could spike irrationally in the short term. Shorts need to be aware of that risk and size accordingly, potentially hedging with options if available.

Broader Market Rally / M&A Speculation: If the overall stock market rallies strongly (perhaps on Fed rate cuts later in 2026), even flawed companies often go up as part of risk-on trade. Also, sometimes the market cycles back to beaten-down recent IPOs as “value bargains” if they drop enough. A general sentiment shift could temporarily buoy STUB, complicating the short timeline. Additionally, if any rumor surfaces (even unfounded) like “Alibaba might invest in StubHub to expand in Asia” or “Netflix exploring live event tie-up” – those could cause short-term pops.

Our Data Could Be Incomplete: As external analysts, we rely on public info. It’s possible we misinterpreted some disclosures or lack context. For instance, perhaps the vendor payment thing was disclosed well enough or is less impactful than the lawsuit claims. Or maybe Jeff Fluhr’s erasure, while bad optics, has zero bearing on operations (which is true – it doesn’t directly affect sales or expenses). If the market decides these issues aren’t material to financial performance, the thesis might not play out as expected.

In sum, we need to monitor these risks. A prudent short investor might limit position size, set stop-loss levels, or use put options to define risk. We believe the risk/reward still favors the short given the weight of evidence, but it’s by no means a riskless bet. Shorts should also be nimble – if the thesis plays out partly (say stock drops into low teens), one might take some profits before, for example, lock-up expiration (since sometimes stocks paradoxically bounce after lock-up as the event is over).

Finally, we emphasize that this is not a call on StubHub as a going concern – we are not saying it’s a zero or fraud. It’s a call that the stock is overpriced relative to reality. If the price did fall to, say, $5, ironically the risk flips (it might become a deep value play if still generating cash). So risk management means reassessing at various price points whether the short thesis still has runway.

Questions for Management

To conclude, we pose a series of questions for StubHub’s management that we believe shareholders deserve clear answers to. These questions highlight the areas of concern raised in this report and could be used by analysts on earnings calls or by investors at the AGM to press for transparency:

Founding History: Why does the StubHub prospectus not mention Jeff Fluhr as a co-founder, and would management acknowledge his role today? How do you reconcile the IPO narrative with prior public information that StubHub was co-founded by two people?

Founder Control and Dual-Class: Mr. Baker, you control ~87% of voting power via Class B shares. Under what circumstances, if any, would you consider sunseting or equalizing the share classes? How can Class A shareholders be assured their interests are considered if they effectively have no voting power?